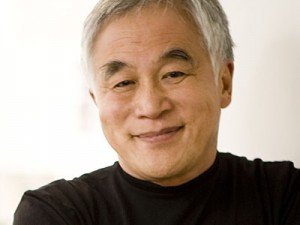

Bing Thom, the Landscaper's Architect

Landscape Trades Magazine

All landscapers wish that architects were more understanding of their job. One of Canada’s leading architects feels the same way.

Bing Thom was born in Hong Kong and raised in Vancouver. His uncle was an engineer and when Thom was eight, he visited his uncle’s office. There, he saw architectural drawings and decided to make drawing such plans his life’s work.

At the same time, he had a feel for gardening and the landscape, a sense which he attributes to his Asian ancestry. At 17, he jumped at the chance to work as a landscaper’s helper. “I spent a summer designing gardens,’ says Thom. “Building rock walls and transplanting trees was good experience—it taught me hard work, and why that work is necessary.”

In 1966, Thom graduated from the University of British Columbia (UBC) with a degree in architecture. After obtaining his Master’s in Architecture from Berkeley, he spent two years teaching at the University of Singapore, then returned to Vancouver and taught at UBC for another two years.

In 1973, famed architect Arthur Erickson asked Thom to help him on a project. “Erickson was my teacher at UBC,” explains Thom. “He, like Frank Lloyd Wright, was influenced by Oriental architecture and they shared a tendency toward the landscape. This appealed to me.”

Thom worked with Erickson, and landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, on the now-famous Vancouver Courthouse/Robson Square. “This project involved a lot of landscaping,” remembers Thom. “Vancouverites wanted a park. The government wanted an office building. So we put the park on top of the office building.

“The courthouse was interesting—three mid-downtown blocks and we were putting a garden atop a man-made structure. The main questions were of waterproofing and finding the right soil mix. So we developed a totally new soil that is both lightweight and able to sustain nutrients.

“There were thousands of plants in that garden,” continues Thom. “We found an entire orchard of pines, magnolias and rhododendrons which we transplanted. Also, Spokane [WA] had 200 matching London Plane trees, which are used in cities all over the world. We bought those but, at planting time, the city’s chief engineer stopped us. He said they grew too fast and that the roots would interfere with sewers and water lines. So we planted 200 Sunset Maples and Victoria happily took the London Planes. Engineers don’t understand plants. They think there should be plastic everywhere.”

Thom’s next project was Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall which he helped Erickson design in a park setting. In 1980, he again helped Erickson, this time on Los Angeles’ Bunker Hill project, which involved re-developing five mid-town blocks and adding linear parks and green space.

In 1982, Thom opened his own office and now employs a staff of 20, including nine architects and his wife, Bonnie.

It is Bonnie, not Bing, who has the green thumb. The daughter of a farmer, Bonnie is an educated landscaper and works on all of Bing’s projects.

“I have a feel for gardening, but Bonnie has the talent. I tell her how I want to project to look and she compiles a list of the plants that will get me that look, according to their colours and textures.

“More architects should consider the colours in the surrounding landscape. I never use red brick because only green plants match it. Instead, I keep my buildings neutral so that when plants flower, their colour takes over.”

Thom is an architect first, but he will not design a building unless he also designs the landscape. “It’s a personal thing. The building must grow from the ground, and the landscaping is the foundation. Each building must sit correctly on that setting, while relating to the landscape. So the landscape is actually more important than the building. Many architects don’t realize that landscaping is essential to architecture—that buildings and gardens are inter-related and indivisible.

“I start every design by looking at the property’s characteristics—the way the sun shines, the wind blows, the location, the view. I use plants only, never anything artificial. And I always use vegetation from the building’s locale. We must remember that we can’t fight nature. We have to work with it.”

What do Thom’s clients think about his approach?

“They appreciate it,” says Thom. “They may mind spending the extra money, but they never argue. I just remind them that’s money well-spent. Many people don’t realize that landscape architecture is more difficult and time-consuming than structural architecture, and that it takes more creativity to do a good landscape than it does to do a good building. I don’t have to account for growth with granite.”

Every one of Thom’s gardens also has a purpose. “I want my gardens to be places for meditation and contemplation,” he says “It’s important that people find tranquil spaces, even in the busiest of cities. That’s why we take care that my gardens are harmonious—never jarring or extreme.”

Surprisingly, Thom has no garden of his own. He and Bonnie live in a penthouse, with four balconies, and not a single plant. “I’m the barefoot shoemaker,” says Thom. “We’ve been planning a roof garden but we’ve never had the time to create it.”

This fits with a trend that Thom has seen increasing—and one that he thinks the landscape industry should be capitalizing on.

“People are living closer together and are nostalgic for gardens. I see more rockeries, solariums, and balcony and roof gardens, and there’s a demand for hobby plants, like bonsai. People want more colour in plants that take up little space.

“I advise landscapers to get into more public education. There’s a thirst for what landscapers have to offer. People are concerned about the look and health of their environment and there’s a need for professionals to go to the public with courses and lectures.”

Thom also advises the landscape industry to lobby for universities to include landscape architecture in their architecture and engineering programs.

“Most architects can’t be bothered with the extra work of landscape architecture. The problem is that no landscape courses are required to get a degree in architecture. This should change. An architect can easily find himself working on a project where the client wants a park or garden. He needs to know how to do that, or he’ll wind up in a situation where the right hand doesn’t know what the left is doing.

“Universities don’t require architects to take interior design courses either. That also makes no sense. It’s like medicine, where specialists come to think of the body in parts, rather than as a whole.

“People wonder why I bother with the landscape but it’s perfectly logical. The building, the interior and the landscape are inseparable, and the same creativity has to be behind all three elements. This should be taught as part of any school’s architectural program.

“The real key, though, is to teach engineers about landscape. Engineers do the most damage to the landscape. Traffic engineers do tremendous harm. They want to keep their roads straight and will mow down any number of trees to do it. They need to learn that roads don’t have to be straight.”

Thom still lectures at UBC and has just completed a three-year term as Chairman of the Vancouver Public Library Committee. His most recent achievement, however, was his award-winning Canadian Pavilion at EXPO ’92 in Seville.

Bunker Hill (rendering)

“I wanted to build a Canadian building in Spain, but I couldn’t transplant Canadian plants, so I made a garden using hard landscaping and evocative images to get the Canadian feel.”

For the first time, Thom had to use man-made materials. He created a jagged white front which looks like a snowdrift during the day but, when lit at night, looks like the Northern Lights. Inside, the pavilion’s focal point is a wall of shimmering blue/green water—it’s actually panels covered with etched aluminum foil. People were so enthralled by the effect, they waited up to 10 hours to get in a second time; it was one of the most-visited pavilions at the exhibition.

Thom has won numerous awards but his greatest compliment is seeing people enjoying his landscapes. “It’s satisfying to see people relax in my gardens. I see them become happier, friendlier.”

Still, he is never satisfied. “I wish I could redo every garden. No matter how careful we are, gardens never grow according to plan. That’s what makes it challenging—the hope is always that the next garden will be my perfect favourite.”